An email sent by the students of a running batch of

General Purpose Ratings training at a DG approved institute in Delhi has gone

viral. That may be an overstatement, actually, because nothing connected with

shipping- the invisible industry- is on anybody’s radar long enough to really go

viral. Whatever; the email was forwarded to me by four different sources on the

same day on the second weekend of this month.

I will not name the institute, for reasons I will

explain later.

Forwarded

emails are often suspect and usually exaggerated. Unfortunately, although this

one may well be overstated, I

fear that it is genuine enough

at the kernel. Sent to a dozen senior officials at the DGS, MMD, IMU and Board

of Examinations for Seafarers Trust (that conducts both entrance and exit

examinations for GP Ratings trainees), the letter is addressed to the DGS and

begs (the words “humble request” are used) that the abysmal conditions at their

academy- infrastructural, academic, faculty related, administrative and the

woeful state of ‘placement’ related issues- be addressed. The subject of the

email says it all-“Please Help All the GP Ratings of July 2012 Batch.”

Of the fifteen points listed in the missive, many

relate to infrastructure. The allegation is that the institute has an absence

of even basic facilities, and suffers from leaking roofs leading to flooded

dormitories and wet bunks, worms in the swimming pool, dirty stinking toilets

that are almost never cleaned (with just one bottle of Harpic being issued every

month for the purpose), dangerously low ceiling fans above the upper bunks and

unbearably hot and humid classrooms. These accusations would be bad enough, but

worse follows- no drinking water in the dormitories and none available at

night, presumably since the main building is locked. Unhygienic, insufficient and

substandard quality of food is another.

I don’t completely buy the convenient reasoning that

some institutes put out in response to such complaints, which says that future

seamen should be used to harsh- even hostile- living conditions. There is no

excuse for keeping trainees underfed and malnourished anyway. But even I would

perhaps grudgingly accept this facile argument if the training at such establishments

was even remotely acceptable. It is often not. “Most of the classes are not conducted and we are

always subjected to cleanship” (euphemism for cleaning or maintaining the

institute) even during class hours, allege the students in Delhi. Claiming that

the library and computer lab are never available to them and are in fact being

used by another non-maritime institute, the accusations go on to say that

faculty is insufficient for training-

which is why, perhaps, so much time is spent on cleanship.

Complaints

from the students and their parents fall on deaf ears or elicit veiled threats

from the administrators, says the letter. An administrator is quoted in Hindi

saying that he- a rich man- will kill the students and make their bodies

disappear and nobody will even know. A Director at the institute dishes out

abuse and threatens expulsion and the destruction of careers, students say,

adding that he has ‘mercilessly’ beaten earlier trainees. Large amounts have

been taken from the students for arranging jobs - the widespread racket that is

called ‘placement’ - but nothing is done. “We are frightened to know all the

past facts from our instructors, teachers and the students of previous batches,”

the email says. “You (DGS) are our last hope…. This training environment (is)

not teaching us anything rather threatening us daily and we are living in a very

poor and pathetic condition.”

I have, after much thought, not named the MET

institute, mainly because I do not know if all these allegations are true. You

can decide whether it sounds like the truth, fabrication or exaggeration; I

will only say that all that is actually the secondary issue here.

The fact is that such conditions exist in more than

a few maritime institutes across the country, and everybody knows that. The

fact is that it is unimportant whether those appalling conditions exist in that

particular institute in Delhi, because they exist elsewhere, and I will bet the

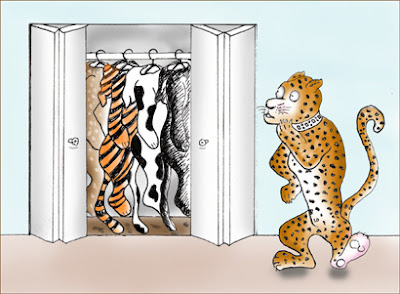

last shirt off my ageing back that they are much more widespread than you or I

imagine.

All maritime institutes approved by the DGS that

conduct GP Ratings courses are subject to strict guidelines regarding

infrastructure, course structure, hours of tuition, syllabus, equipment- and almost

everything else. Each deficiency mentioned in the email, for example, concerns

something that the DG s examines before initial approval, and at each annual

audit thereafter- or surprise audits that it can choose to conduct anytime. The

institute must keep proper records of everything. At these audits, it is common

for surveyors to examine dormitories for liveability, toilets for cleanliness,

general infrastructure, lesson plans and records of classes conducted by each

faculty- who are not supposed to teach more than so many hours a day. I have

seen DGS surveyors examining everything from classrooms, equipment,

dormitories, faculty credentials, wiring, fan heights, toilets, faculty

sufficiency, their appropriateness and their hours of work. I have seen them

going through student feedback forms. It seems impossible that a MET

establishment can run like the one in Delhi is alleged to have; it seems

inconceivable that an institute can function with glaring deficiencies under

almost every head of the DG guidelines. But many do.

Why? Short answer- this is India. There is not

enough space out here for the long answer.

I am beyond

anger here, and well into despair. For imagine

a 17 year old youngster, little more than a child, just out of the tenth grade

wanting to make a career at sea. His unschooled poor or lower middle class

parents are thrilled when he gets through the common entrance examination. They

take a loan to fund his training, content that the subsequent career will make

the loan repayment easy. The youngster joins a DG approved institute; if this

is like the one described in the email I have been talking about, he is bewildered

and increasingly disheartened at the conditions and lack of training. He hears

disturbing stories about joblessness in the future, but it is too late, because

another loan has been taken by the time he graduates- this one for ‘placement’.

His parents are now in hock for a figure that can be rounded off to half a

million rupees, counting interest.

Two years later, he is still jobless and has

abandoned all hope. The interest on the loan is still being repaid, with no end

in sight.

Just imagine. Imagine all that.

Now imagine if that boy were your son.

.

.